|

| Homer Charles Squire |

One of the most confounding problems that I have faced while researching the origins of Knoxville baseball is in compiling the rosters of the original two teams—the Knoxville Knoxvilles and the Holston Base Ball Club. For the most part, Charles Seymour and Sam B. Dow provided the first and last names for a good number of the original baseballists in their reminiscences, published in local newspapers in 1895 and 1921, respectively. Furthermore, the Knoxville Daily Herald’s December 6-7, 1867 listings of prospective bachelors provided yet a third source to confirm the names since the brief descriptions for a number of the eligible suitors identified either “base ball” or the national game as one of the hobbies that they were actively engaged in playing. But in some cases, however, a single last name or an incorrect first name given to or misprinted by the press in either a box score or an article have prevented me from identifying a particular baseballist with a 100% degree of certainty. Such was the case for a long time for a certain “Squires” who played both first base and shortstop for the Knoxville Knoxvilles.

In Dow’s 1921 interview with the Knoxville Sentinel, he identified a “Tobe Squires” as the first baseman of the Knoxville Knoxvilles Base Ball Club that he founded. From that point forward, I was fixated on finding another source, or two, (or better yet three!) that would confirm that there was indeed a living and breathing human male named Tobe Squires in Knoxville in the late 1860s. But such was not the case. One of my immediate go-to sources in confirming the identities of Knoxville’s original baseballists is the city directory. I use this source because the nearest federal census to the beginning of baseball in Knoxville (1867) was taken in 1870. In many cases, a city directory will provide the first and last names (even, at times, middle initials and/or names) of its residents, as well as the location of their homes and their occupations. For Knoxville, there are some huge gaps in the availability of its annual city directories. The first available directory for Knoxville is 1859; the second is 1869. Though this gap is regretful and has hindered scores of searches that I have conducted for countless research inquiries, the 1869 city directory has been critical for identifying the original baseballists. Armed with the name Tobe Squires, I searched in vain to find him, but alas, nothing! The closest that I could find was an “H.C. Squire,” which I filed away (buried more like it!) as a note in an Excel spreadsheet that I started to compile the rosters. I continued in search of Tobe because surely Sam B. Dow had the name “Tobe Squires” correct, right?

|

| Knoxville City Directory (1869) |

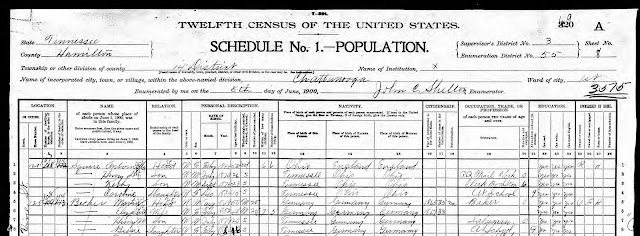

Another valuable source in my research has been digitized Knoxville newspapers on Newspapers.com. When Ron Allen, Sr. compiled his early history of Smokies Baseball, he had spent countless hours cranking away at the microfilm readers in the library to read the small print of the city’s newspapers. Of course, this meant that some articles documenting a game of baseball or anything related to the clubs could easily be missed. The benefit of digitized newspapers is the OCR readers save valuable time for the researcher and a simple term search will guide the researcher to an article from the comforts of one’s own home. That said, the pitfall here is that your search is only as good as the subject terms that you put into the search bar and, most importantly, it is especially only as good as the OCR software embedded into the system. While newspapers.com is a great source, there are certainly some issues with its search capabilities. For example, one day I may enter a specific term into the search box, with a specific set of dates, and the city of Knoxville and get a specific set of results. The next day, however, I could enter the same term, set of dates, and city and get a hit on an article that was not pulled during my previous search. In the process of entering terms such as “Tobe Squires,” “Squires,” “base ball,” and/or “baseball,” I found two additional names that I had not yet encountered—“W.H. Squires” (a short stop for the Knoxvilles listed in an Aug. 1867 match) and “H.C. Squires” (elected as the Knoxvilles’ Club Secretary in Apr. 1868). One more perplexing problem was that the only “Squires” that I could find when looking at the nearest federal census for Knoxville to the beginning of baseball in the city—the 1870 U.S. Census—was a listing for a “S.C. Squires.”

.jpg) |

| Knoxville Whig (Aug 7, 1867) Identified as "W.H. Squires" |

.jpg) |

| Daily Press and Herald (Apr. 26, 1868) Identified as "H.C. Squires" |

While I continued to find nothing for “Tobe Squires,” “W.H. Squires,” or even “S.C. Squires,” I began to hone in on the fact that Club Secretary “H.C. Squires” and “H.C. Squire” from the city directory might just be one in the same. While I could not discover another source with the name “H.C. Squires,” I did manage to find “H.C. Squire” in Knoxville in the 1880 U.S. Census.

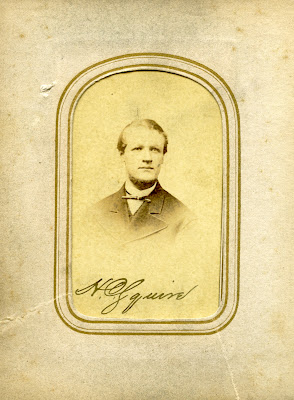

Everything began to come into focus during my Summer 2020 COVID research trip to North Carolina to visit the home of Sam B. Dow’s great-grandson. There, in his basement, the repository of Dow’s personal papers and much, much more, was a stack of carte de visites (mid-19th century photographs) that once belonged to Dow. As I thumbed through them carefully, I could see the faces of those near and dearest to Sam B. Dow. Among the images that he had collected were members of his family, his fellow Masons, and, at least one of his close friends who he enlisted to join his base ball club (I am sure there may be at least one or possibly more Knoxvilles or Holstons in that stack, but they were unmarked and some were unfamiliar to me at that time). I did not immediately recognize this close friend and fellow Knoxville baseballist on first glance. I did, however, recognize the name signed on the front of the carte de visite. As I raised the card up for a closer look, there it was clear as day, the autographed signature of “H.C. Squire” and above that, his likeness staring back at me with what might be perceived as a sly smile, as if Squire was acknowledging that I indeed now had both his name and his image to add to my list of original Knoxville baseballists.

[I would subsequently stumble upon yet another image of Homer Charles Squire while researching for another project (see photograph at the beginning of this blog)]

|

| Homer C. Squire (Dow Family Papers) |

.jpg) |

------------------------------

“H.C. Squire” was, in fact, Homer Charles Squire, born in 1841 to Samuel and Sophia (Hurd) Squire of Chardon, Ohio (Geauga County, approximately 25 miles east, northeast of Cleveland). The Squires were among some of the earliest pioneer families to settle in the Western Reserve. Samuel came west from New York with an ox team soon after his marriage to Sophia Hurd in 1820. Samuel began his trade as a tanner, establishing a tannery first in Painesville, Ohio before settling permanently in Chardon where his sons also learned the trade. In Chardon, Samuel became not only a respected businessman, but also a local official, serving two consecutive annual terms as the county treasurer. By 1850, Samuel had established himself as a dry goods and grocery merchant, entering into a partnership with his eldest son, Samuel Squire, Jr. The younger Samuel continued in that line of business in Oberlin, Ohio where he also opened two banks and was a founder of the Oberlin Building and Loan Association. He later sold his palatial home to Oberlin College, which built a magnificent library funded by the steel baron, Andrew Carnegie on Squire’s former property. Sophia passed away at the age of 49 on June 9, 1848. Samuel remarried shortly thereafter to Nancy Hastings, formerly of Massachusetts; however, he died in 1854, leaving Homer Squire, at twelve years of age, in the care of his stepmother.

Tracing the whereabouts of young H.C. Squire is difficult due to the paucity of available sources beyond the 1850 and 1860 federal U.S. Census records. Thanks to his family’s economic fortunes, Squire was able to attend school and, though I have not been able to confirm the school(s) that he attended, it is quite possible that Samuel’s sons may have enrolled at Geauga Seminary, a Free Will Baptist school that President James A. Garfield, who grew up nearby, attended. By 1860, H.C. Squire had moved out of his stepmother’s home and was living about 10 miles north of Chardon, in Painesville Village, in a hotel kept by Eli T. Booth. In Painesville, Squire worked as a clerk and was just beginning to amass some modest savings when the American Civil War broke out.

The young men of Painesville and other surrounding villages and towns of Lake County, Ohio enthusiastically joined the Union war effort following the first round of enlistments in the wake of the firing on Fort Sumter and President Abraham Lincoln’s call for troops. Squire made his way west to Cleveland where he enlisted on August 21, 1861 at rank of Corporal in the 2nd Ohio Cavalry, Co. G. In October, Squire and the 2nd Ohio were sent south to Camp Dennison, on the northeastern outskirts of Cincinnati, not far from the Ohio River. The camp, named by General George B. McClellan in honor of Cincinnati native and Ohio’s Civil War governor, William Dennison, was a recruiting, training, and medical post for the United States Army. Located in close proximity to the neutral slave state of Kentucky, federal authorities hoped to recruit loyal Kentuckians for the Union cause. Squire spent 3 months there before the 2nd Ohio received its orders to head west of the Mississippi River. Dispatched to the Missouri border largely for scout duty, Squire and his fellow soldiers spent much of 1862 chasing Western Rebels around Missouri, Kansas, Arkansas, and even into Indian territory (present-day Oklahoma). They saw limited action in Missouri at places such as Independence, Montevallo, Horse Creek, and Grand River, as well as captured Fort Gibson from Rebel troops in the Oklahoma Territory. By Christmas 1862, the 2nd Ohio Cavalry was back home in the Buckeye state stationed in Columbus. There they remained until receiving orders in March 1863 to march south into Kentucky ahead of a planned invasion of East Tennessee to liberate the region’s loyal Unionists from Rebel occupation.

|

| Homer C. Squire, Civil War Service Records |

But before the recently promoted Sgt. H.C. Squire could join his men in the 2nd Ohio on its trek south of the Ohio River, he was discharged from the Union Army for an undisclosed disability. For whatever reason, Squire was back home in Painesville by the summer of 1863 and working as a clerk. Though he may no longer have been deemed fit for military service, Squire would later pack up his bags and join several of his fellow Ohio soldiers in post-Civil War Knoxville, Tennessee where they had decided to make their future in the Mountain City. These men were young, energetic, intelligent, full of faith, and possessed just enought capital to invest in rebuilding a New South. In Knoxville, Squire and Stephen J. Todd (2nd Ohio Cav., Co. E) set themselves up on the first floor of the Old Union bank building along Main Street where they served as claims agents employed by those seeking to collect on their claims against the federal government. Here Squire and Todd joined with a number of other former Union soldiers calling Knoxville home and renewed their friendships via a number of male fraternities such as the Masonry and playing the gentlemanly amatuer game of base ball.

.jpg) |

| Knoxville Whig (Oct 18, 1865) |

There is not much to say about Squire’s baseball career. The extant sources reveal only little nuggets of information here and there. For one, Squire’s friendship and bond with a number of former Union veterans from the Midwest opened a door to join the Masons where he established a friendship with Sam B. Dow, a revenue officer in the employ of the federal government and the founding father of Knoxville baseball. Dow recruited Squire, whom he noted in his 1921 Sentinel interview was one of the original members of the Knoxville Knoxvilles. Dow listed Squire as having been placed at 1st base. The only other articles with respect to baseball in which Squire appeared was one noting that he would be playing shortstop for the Knoxvilles in an upcoming match against the College Hill Club of Greeneville (though no box score was published, a subsequent report indicated that the Knoxvilles lost to their Greeneville rivals by 18 runs) and another that announced he had been elected the Club Secretary following the April 1868 election of club officers. Whether Squire played any matches beyond 1867 is a question that the available sources cannot resolve.

But a number of primary sources can help flesh out more of Squire’s life and times in Knoxville and beyond. While Knoxvillians became afflicted with the “base ball fever” in the summer and fall of 1867, and as the city made plans for a baseball tournament, Squire returned to Painesville, Ohio where he married Antoinette Elizabeth Bracher, the daughter of Thomas E. and Elizabeth Kirby Bracher. There is little known about Antoinette’s life prior to her marriage to Homer. Her parents were both native to England; however, Antoinette, or Nette as she was known, was born in Painesville in February 1843. The young newlyweds promptly returned to Knoxville where they moved into hotel keeper J.C. Flanders’ Lamar House. Soon thereafter, Squire was hired as the Chief Clerk of the United States Pension Office in Knoxville. His appointment in that office came thanks to Dr. Daniel Tucker Boynton, who, as a surgeon with the 104th Ohio was stationed in Knoxville and came to the attention of William “Parson” Brownlow, who hired him as his personal secretary during his term as Governor of Tennessee. Following Brownlow’s election to the United States Senate, the outspoken Tennessee Unionist solicited President Ulysses S. Grant to appoint Dr. Boynton as Knoxville’s pension agent (Boynton served in this position throughout Grant’s two terms, as well as the administrations of Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, and Chester A. Arthur). Squire served with Boynton during the Grant administrations but then left to accept brief appointments as the teller of both the Mechanics and East Tennessee National Banks. In 1884, Squire left Knoxville for Chattanooga, where he was appointed as cashier of the First National Bank of Chattanooga.

H.C. Squire was fast becoming one of Chattanooga’s most prominent citizens when a bout with typhoid fever weakened his constitution, resulting in severe abdominal pain and weight loss. Debilitated, the disease took him from this earth in his Vine Street residence on October 12, 1887. The turnout to Squire’s funeral the following day was further proof of the esteem that the community held Squire and his family. A number of veterans with the G.A.R. were present as Squire’s body was lowered into a grave prepared in a section of the Chattanooga National Cemetery.

.jpg) |

| Chattanooga National Cemetery |

For most of their time in Knoxville, the Squires lived on East Clinch, between First Creek and McKee Street (present-day Cal Johnson Recreation Center and Park). Together, Homer and Antoinette had six children: Mary (1869); Samuel H. (1872); Henry D. (1873); Kerby Boynton (1876); Annie (1878); and Carrie (1883). The Squires were devout Christians who attended the First Presbyterian Church in Knoxville and the Second Presbyterian Church in Chattanooga.

|

| Kerby Boynton Squire (Ancestry) ("Kirby" was a name derived from his mother's family; however, officially, he always spelled the name with an "e.") |

Antoinette was left with a comfortable savings that H.C. Squire had amassed in his various business investments. That said, her sons remained single and thus each continued to board at the Vine Street home with their mother long after becoming adults. Their various jobs such as cashier, postal clerk, bookkeeper, and real estate agent helped supplement the family’s income. Each of Antoinette’s daughters, however, married and started their own families soon after coming of age. Mary, their eldest, married Frank Joseph Weber, who began as a printer for the Knoxville Sentinel before becoming an editor of the Chattanooga News. They had one son, whom they named Homer Squire Weber in honor of Mary’s father. Annie began her career as an art teacher, but later became a housewife after she married Wayne Headrick, who dabbled as a clerk in the wholesale grocery business and a florist before retiring as a farmer.

Their mother, Antoinette, passed away as a result of heart disease on Jan. 3, 1917. She was interred alongside her husband in the Chattanooga National Cemetery.

|

| Obituary Chattanoga News (Jan 3, 1917) |

|

| Antoinette's Death Certificate |

|

| Antoinette E. Squire, Chattanooga National Cemetery |

TRAGEDY in the Home of the Squire’s Youngest Child

The real tragedy for the Squire family is that of Homer and Antoinette’s youngest child, Carrie. Much like her older sister, Annie, Carrie enjoyed art. She began her career as an assistant to Chattanooga’s most prominent early twentieth century art teacher, Cora Sophia Stratton, before embarking on a career as an art teacher herself. Soon thereafter she married Frederick Carpenter French, a draughtsman and city inspector of Chattanooga’s streets and sewers. Together, they had three children, Dorothy Carpenter (1908), Annie Louise (1910), and Edgar Lee (1915). Edgar sadly was born with an affliction that left him with poor eyesight. Frederick and Carrie consulted numerous doctors but to no avail.

The tragedy for the French family began in 1917, when their daughter Annie suddenly became sick and died on Aug. 10. On the heels of their daughter’s death, Carrie became sick with influenza (the Spanish Flu) during the winter 1917-18. Though she survived, her husband later said that Carrie did not immediately recover. In fact, Frederick claimed that his wife suffered the consequences of her illness for another five years. Though she seemed outwardly healthy by 1929, it is quite possible that she never fully recovered—the combination of suffering the death of her daughter and enduring the consequences of the flu might well have left Carrie despondent and with depression that she privately waged war against. If Carrie was indeed descending into a crisis, Frederick was not aware of it. Some ten years removed from the one-two gut punch of losing a daughter and battling a severe flu, Carrie apparently had Frederick fooled because he believed that she was in a healthy state, both physically and mentally.

On the evening of September 3, 1929, Edgar, age 14, was sitting at a desk in the front room of their home located on Missionary Ridge when his mother came up from behind him with a .32 caliber pistol in her left hand and shot him three times. One bullet entered into Edgar’s back and pierced his chest; a second bullet grazed the top of his head; and the third bullet entered into the base of his skull. Edgar fell out of his chair and laid partially paralyzed on the floor in a pool of his own blood. He could see his mother turn and leave the room, making her way towards her bedroom. There, she stood before the mirror and raised the pistol to her left temple and pulled the trigger.

%20(2).jpg) |

| Chattanooga Times (Sep 4, 1929) |

Frederick arrived home at around 9:30 p.m. that evening and knew something was amiss even before he reached the front door. As he passed by the front window he caught a glimpse of his son laying helplessly on the floor in a pool of blood. Frederick entered his home and found Edgar slipping in and out of consciousness. In a series of broken sentences, most of which were largely inaudible, Edgar was able to tell his father that his mother had shot him. As Edgar finally lost consciousness for an extended period of time, Frederick went looking for Carrie, who he found unresponsive in the middle of their bedroom.

Both Carrie and Edgar were rushed by ambulance to Erlanger Hospital where Carrie was officially pronounced dead shortly after 2 a.m. the next morning. Edgar’s surgeons were not initially optimistic about his chances of survival. However, Edgar proved persistent and defied the odds to survive his wounds. He passed away at the age of 68 in 1983 and is buried next to his sister, Annie, across from both his father and mother. Frederick and Carrie’s oldest child, Dorothy, was not present at the time of the murder-suicide. She was away studying bible vocational work in Salisbury, North Carolina. Dorothy would later marry Alexander Gregory Williams and the two began their lives together in Florida before permanently settling down and devoting their lives to God in Huntsville, Alabama.

SOURCES: Homer C. Squire & Family U.S. Census Records (1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, & 1900)

|

| 1850 Census |

|

| 1860 Census |

|

| 1870 Census |

|

| 1880 Census |

|

| 1900 Census |

Comments

Post a Comment