|

| Samuel Bell Luttrell (ca. 1880) |

Unlike their rivals, the Knoxville Knoxvilles, whose common bond among its members were their participation in the Union Army, their midwestern roots, and membership in Knoxville’s secret Masonic society, the Holston Base Ball Club was unified, in many respects, by familial bonds. There were three sets of brothers that played for the Holstons—the Whites, Armstrongs, and the Luttrells. These latter two families were not only part of Knoxville royalty, so to speak economically, politically, and socially, but also were connected by marriage. The Armstrongs (Robert Aiken and Frank Wells) and the Luttrells (James C. and Samuel B.) were second cousins. Such familial bonds were a natural tie that bounded the club together as they organized a roster of at least nine members to be able to play the game of baseball. Of course, there are other ties that bound the Holston roster; these include both friendship, age (students), and politics (Civil War loyalties to the Rebel secessionist cause and post-Civil War opposition to “Brownlowism”/Radical Republican rule in Tennessee).

Our first featured baseballist to play for the Holston

Base Ball Club is hardware merchant

and banker, Samuel Bell Luttrell. Considering all of the original members of

the Knoxville and Holstons (whom I have been able to confirm their identities,

as well as both their birth and death dates), Luttrell outlived all but one of

these founding members of Knoxville baseball. As local journalist Jack Neely

summed up the life of Luttrell in one of his many books on the city’s history,

he wrote that “the Civil War veteran survived to see the era of automobiles,

airplanes, radio, and movies,” dying in 1933 with an estate valued in excess of

$1,000,000. A president of 29 local businesses and an investor in over a

hundred other firms, Luttrell was one of the most successful of all of

Knoxville’s original baseballists of 1867. When asked to what he attributed his

success in the business world, Luttrell simply replied, “Work; there can be no

such thing as success without it!”

%201.jpg) |

| Knoxville Journal (Jan. 7, 1934) |

The Luttrell House Divided

Luttrell was born in Knoxville, July 23, 1844, the son of James Churchwell and Eliza Carr (Bell) Luttrell. Descended from Scotch-Irish-English and French stock that had fought against the British in the American Revolution and yet again in the War of 1812, his ancestors were among the first to have settled in East Tennessee following independence. Samuel’s father, James Churchwell Luttrell, Jr., was both a successful lawyer, merchant, and politician, who served as Knox County registrar, deputy marshal, state comptroller, postmaster, mayor, and state senator. When the American Civil War erupted, his father, who had acquired a personal estate in excess of $16,000, was in his third consecutive term as mayor of Knoxville. Though Luttrell was a Unionist who believed slavery best preserved within the Union, he managed to govern as an independent moderate. Thus, in a city torn asunder by the war, he somehow managed to hold a divided city together under both Confederate and Union occupation while facing yearly elections (Luttrell served as mayor from 1859-1868). And yet, the elder Luttrell’s own house was divided.

James and Eliza had six children—four daughters and

two sons. These two sons—James C. and Samuel—would don Rebel and Union uniforms

respectively. James C. Luttrell III, who had begun his career working for his

father as a salesman, would be made a lieutenant in the 4th Tennessee

Infantry (“Rhett Light Artillery,” CSA) while Samuel, an active seventeen-year-old

student in the debating society at East Tennessee University and a newsboy,

eventually became a corporal in the 12th Tennessee Cavalry (US) once he came of

age. Though the elder Luttrell and Samuel’s politics may have diverged from the

rest of the Luttrell, Bell, and Armstrong families, they converged at the close

of the war as a result of the Republican party and Lincoln administration’s

emancipationist and Reconstruction policies. By 1869, the elder Luttrell and Samuel

were breaking bread with the former Rebel Democrats (Mayor Luttrell was elected

as a Conservative Republican to the state Senate in 1869; however, he voted

with Democrats to expunge Brownlow Republican laws from the statute books and

supported the 1870 state Constitution which wiped out the last vestiges of “Radical

Republican” rule to redeem Tennessee).

At the close of the war, Luttrell was appointed as a money

order clerk in the Post Office, a position he no doubt owed thanks to his

father who served as postmaster in addition to his mayoral duties. Soon thereafter,

a new postmaster for Knoxville was appointed and Luttrell became a clerk for William

Wallace Woodruff’s Hardware Company. Woodruff, a former Union officer as well, quickly

made a name for himself as one of Knoxville’s leading post-Civil War merchants.

Under Woodruff’s tutelage, Luttrell learned the trade and would soon open his

own hardware business in 1870, a business he operated for fifty years.

%201st%20ad.jpg) |

| Knoxville Daily Press and Herald (Dec. 19, 1871) |

.jpg) |

| Knoxville Daily Chronicle (Dec. 17, 1871) |

Samuel Bell Luttrell, the Baseballist

As for Samuel Bell Luttrell’s baseball playing career, there’s not too much to say due to the paucity of extant sources. He was among the founding members of the Holston Base Ball Club, which organized shortly after Dow’s Knoxville Knoxvilles. It is quite possible that Luttrell was recruited to join the club thanks in part to his second cousin, Robert Aiken Armstrong, who was elected the Holston Club’s first captain. There are, however, no box scores to draw from to speculate as to Samuel’s prowess in the batter’s box or his artistry as a scout on defense in the field. But there are brief nuggets offered in both Charles Seymour and Samuel B. Dow’s reminiscences (1895 and 1921 respectively), as well as a match report from the summer of 1867, that provide us with a mere glimpse into the Holston baseballist’s playing career. Interestingly, these are stories that involve painful injuries incurred on the field of play.

If we carefully examine the origins story of Knoxville baseball that both Seymour and Dow told reporters we can piece together a single play from one of the first matches between the Knoxvilles and Holston clubs in 1867 that did not end well for Luttrell. It all began when William “Bill” Chamberlain of the Knoxvilles came to the plate. Chamberlain, Dow recalled, was known for swinging with such force that he could “hit a ball a terrible blow.” Such was the case during this at bat. Chamberlain sent the ball an incredible distance in the air. Luttrell tracked the cloud hunter from his position in center field. He quickly got under it; however, as the ball began its descent, Luttrell lost it in the sun. He stretched out his hands above his head to make the barehanded catch on the fly, but the ball slipped between his fingers before he could close them together and it struck him in the forehead. “He dropped like a beef,” Seymour recalled. The Holston center fielder was briefly knocked unconscious before his teammates carried him from the field. That injury, according to Seymour, ended Samuel Luttrell’s baseball playing days.

There is, however, a second story that involves another injury in which Luttrell was also involved. Thankfully for Luttrell, the Holston

baseballist was not on the receiving end this time. In a July 4, 1867 exhibition

match that pitted the Holston Base Ball Club against the Emmett Machinist Club,

in which thousands of Knoxvillians turned out to watch the national game played

as they celebrated Independence Day, Luttrell stepped inside the batter box to

take a pitch from the Emmett’s hurler, the appropriately named William Hurley. Luttrell

swung at Hurley’s pitch, sending the ball in a direct line back toward the

Emmett pitcher who was struck squarely in the face. The injury forced Hurley’s

retirement and the game soon got away from the Emmett, who called the match at

the close of the 5th inning, with the Holstons at 65 runs scored to

the Emmett’s 12. Though his older brother (James C. Luttrell III) was soon elected

the Holston’s second club president, there is no record that Samuel Bell Luttrell

played baseball after the inaugural 1867 season. In fact, Luttrell may well

have quit playing by the end of summer 1867 because he does not appear in any

of the match reports, rosters, and box scores for the best-of-three state championship

series that the Holstons won over the Mountain City Club of Chattanooga in September.

Devoted Family Man

By 1868, Luttrell’s time was preoccupied with family

and establishing himself as a successful businessman. In October 1866, he

married Margaret McClung Swan, whom he proudly boasted throughout their sixty-seven

years together, was “THE most beautiful woman in Tennessee.” Together, they had

five children—three daughters (Margaret, Jennie, and Mamie) and two sons (Samuel,

Jr. and Charles), who both tragically did not live long lives.

Both Luttrell and his wife, Margaret, were active members

of Church Street M.E. Church, attending regularly until a few years prior to

his death on account of deafness, which robbed him of the ability to hear the

services. He was known to be sentimental and devoted to his wife and family. This

sentimental devotion led him to carry a photograph of his deceased son, Charles

(who died after a two-year bout with consumption), in his pocketbook that he

often took out to look at when he had a quiet moment alone.

Merchant Prince, Banker, & Industrialist

Beyond being successful in the hardware industry, Luttrell

dabbled in the wholesale grocery business and real estate (Southern Building

and Loan Association). Luttrell purchased hundreds of acres on the southside of

the Tennessee River and, as his own death neared, he donated a large tract of

that land for a park (Luttrell Park). Moreover, he invested heavily in his

native Knoxville. He owned substantial shares in the White Lily flour factory, Brookside

Cotton Mills, Knoxville Brick Co., several coal companies (Coal Creek Mine and

Manufacturing Co., Jellico Coal Co., Winters Gap Coal and Land Co., and Poplar

Creek Coal and Iron Co.), and he even, at one point, when everything seemed up

for sale, owned a majority interest in the Gay Street Bridge, which he

purchased from George W. Saulpaw. In July 1891, Knox County moved to make the

Gay Street bridge a free bridge. The Knox County Court ruled that Luttrell be

paid $20,000 over a period of two years, during which time he would receive all

tolls collected. In the summer of 1893, ownership of the bridge transferred

from Luttrell to the county. He was also an investor and director of the

Knoxville Schuyler Electric and Power Company, which commenced operations in

1885 and brought widespread street lighting to the city in 1896.

While his hardware company thrived, Luttrell made a

name for himself as a banker. In 1882, the Mechanics National Bank was

organized with Thomas O’Conner as president and Luttrell became one of its

directors. However, when O’Conner soon thereafter died in an infamous gunfight

on Gay Street, Luttrell was elected to assume the role as bank president which

he successfully presided over as it became Mechanics Bank and Trust Company and

later merged to become the Union National Bank (1882-1922).

%20Luttrell%20and%20Frank%20Armstrong.jpg) |

| Knoxville Journal and Tribune (May 10, 1921) |

A Public Life

Like his father and older brother, Samuel Bell Luttrell led an active civic life. He not only was elected First Assistant of the Fountain Fire Volunteer Company in 1870, he also served as one of the original trustees of the University of Tennessee (1879). A prominent supporter of education, he advocated for the establishment of a public library (later becoming Vice President of the Knox County Public Library). He was said to be “a liberal contributor to charity,” often donating when the local newspapers highlighted a family in need, requesting that his name not be publicly mentioned. Judge A.C. Grimm remembered his friend’s generosity: “He did more for his fellow men than the public will ever know.”

Politically, Samuel Bell Luttrell made the natural pivot from a Conservative Unionist to a Democrat during Tennessee’s tumultuous Reconstruction era (late 1860s). Like his father, Luttrell was an independent moderate, which broadened his appeal with Knox County Democrats because as a non-partisan he could garner the support of many Republicans. He began his political career as an alderman, winning three consecutive terms (1868-78). When Mayor Joseph Jaques suddenly announced his resignation to the Board of Aldermen on April 8, 1878 due to an unexpected departure from the city for an extended period of time, the board unanimously elected Luttrell by acclamation to fulfill the remainder of Jaques’ term. In January 1879, Luttrell put his name in the hat for the mayoral race and won a second term as the city’s executive. His nearly two full terms as mayor coincided with the city’s second post-Civil War “building boom” and ushered in Knoxville’s Gilded Age of the 1880s in which its population more than doubled.

A man of great wealth, he erected a large, handsome home on the northwest corner of Laurel Avenue. He was known to be one of the last of Knoxville’s captains of industry and merchant princes to trade in his horses and carriage for an automobile. Each year, Luttrell would carefully ready his horses and carriage to take his wife on the same trip around town that they made as bride and groom on their wedding day. As death came for him on November 20, 1933 at the age of 89, a family member told the press that Samuel Bell Luttrell passed, “calmly, beautifully, unostentatiously, even as he had lived.”

%201.jpg) |

| Knoxville News Sentinel (Nov. 20, 1933) |

Samuel Bell Luttrell Grave, Old Gray Cemetery (Knoxville, TN)

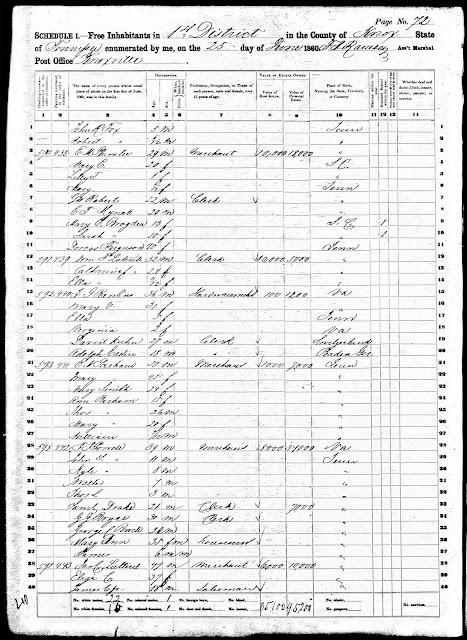

Sources: Samuel Bell Luttrell in the Census (1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930)

|

| 1850 Census |

|

| 1860 Census p. 1 |

|

| 1860 Census p. 2 |

|

| 1870 Census |

|

| 1880 Census |

|

| 1900 Census |

|

| 1910 Census |

|

| 1920 Census p. 1 |

|

| 1920 Census p. 2 |

|

| 1930 Census |

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment